THE SEXY AND FLUXY SHOW

- David Moloney

- Jan 13, 2024

- 13 min read

The Dominators v. War of the Sontarans

Happy New Year, and welcome to another post reviewing a randomly selected pair of Doctor Who stories, one from the twentieth century series, and one from the twenty-first century’s run. This time round, it’s Second Doctor tale The Dominators, written by Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln (but released under the pseudonym Norman Ashby) and first broadcast between 10 August and 7 September 1968, and the Thirteenth Doctor’s War of the Sontarans, written by Chris Chibnall and first broadcast on 7 November 2021. Quarks Ha!

The Dominators

The last time I watched The Dominators must have been shortly after I bought the first DVD release early last decade, and I do remember thinking at the time that it was a bit of a slog, but also that the story is frosted with a surprising amount of kink. It’s the naughty sex one. I suppose the clue was always in the name of the titular Dominators themselves, these agitated young men bedressed in ribbed plastics, travelling the galaxy in their torture ship. There is high tension between Navigator Rago and Probationer Toba from the very first scene, and one can only imagine the volatility of two angry Doms sealed up in that confined space for any length of time. Fortunately their spaceship is equipped with devices to bind bodies to the wall, and flip-down tables on which to ‘probe the physiological make-up’ of natives in togas and kilts.

The loosely-robed Dulcians of Dulkis present themselves as the race of Submissives that Rago and Toba have long been searching for. They are governed by an indolent council of pacifists who sound as though they would be willing to do anything to keep the angry men satisfied. For those Dulcians who get bored of reclining on the easy chairs, it seems fairly easy to join one of naughty boy Cully’s ‘illegal’ pleasure trips – a cruise on his egg-shaped capsule through Barbarella-esque mists in search of excitement and adventure. Everyone on Dulkis appears to be dressed for a Roman orgy, but no-one has quite what it takes to get the party started until the Dominators arrive. The Doctor explains that the invaders’ plan is to drop their radioactive seed into a hole at the most vulnerable part of the planet’s crust, triggering a volcanic eruption, and … well, it’s not even much of a metaphor, is it?

This story was made and broadcast in 1968, in the middle of the supposed revolution of sexual liberation, so perhaps it’s just a natural product of its time. Whovian lore is full of anecdotes of saucy on-set japes among the regular cast of Patrick Troughton, Frazer Hines, Wendy Padbury and Deborah Watling, and it wasn’t uncommon for a bit of cheeky innuendo to slip into the scripts. We probably see it there now even when it was unintended (‘Oh yes, Jamie. Blow that up for me, would you?’ – Doctor hands Jamie an inflatable beach ball). But it’s hard not to conclude that The Dominators’ writers Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln needed to spend a bit of time in horny jail for this story.

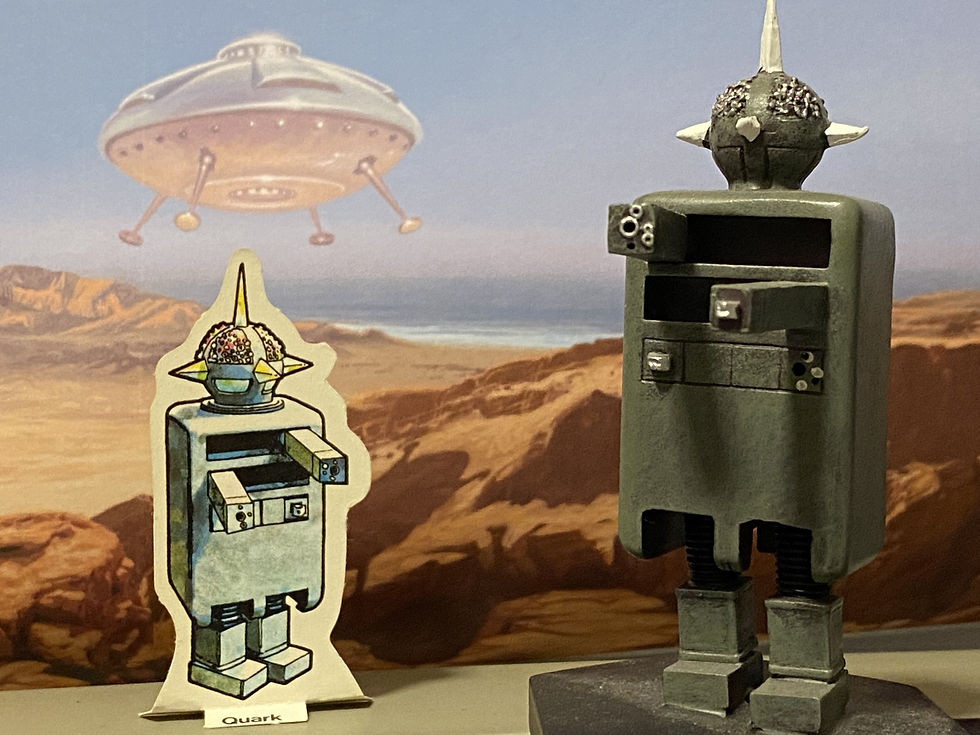

Perhaps they were just in a very good mood at the thought of cashing in, Terry Nation style, on the success of the cute little robots they created for the story, the Quarks. Would Christmas 1968 be remembered as the season of Quarkmania? Last night I watched this year’s Call the Midwife Christmas special and all the little kids seemed to want from Santa was a tortoise and a telescope, so something obviously didn’t turn out quite as Haisman and Lincoln expected. On his excellent Psychic Paper blog, James Cooray Smith recently explained some of the background to the writers’ dispute with the BBC over ownership of Quark rights as the spiky, squeaky little critters started a run of appearances in TV Comic’s Doctor Who strip, but I don’t think they were ever exploited much further than that.

The Quarks are odd little monsters, and it’s hard to identify quite why there was an expectation that they might become the next big thing. They are fairly ineffectual in the story: they have limited mobility, silly voices, and constantly in need of recharging. There are a couple of extended scenes (in episodes three and five) of chases with Quarks around the Dulcian quarry, in which a few of the Quarks explode, which probably would have been exciting for young viewers back in the day. Beyond that, I guess the design is the thing; those fold-out arms are quite neat (if inefficient), and the crystalline design of their heads is distinctively cool. They look good on Weetabix cards and as an Eaglemoss figurine, and seem to have become an iconic part of Doctor Who’s grand history despite never really impressing on screen.

The Dominators themselves, sexual fetishes aside, appear to represent the two faces of British Conservatism – cold, heartless, economic efficiency (Rago) versus a contemptuous desire to destroy (Toba) – locked in an eternal struggle of mutual hatred while attempting to devastate the landscape and populace around them. (Happy New Year, everyone!) At the beginning of episode four Rago subjects Toba to a rigorous on-the-spot performance review, simply as a power flex, it seems, to remind him who dominates the Dominators.

The Dulcians are also presented as a race at war with themselves, although the conflict for these people seems to be how best to live in peace. Society on Dulkis is structured around logic and rational debate, and a submission of one’s natural desires for exploration, fantasy and adventure. The ruling council speaks proudly of their pacifist ideals, yet they tolerate the existence of a museum of war on an ‘Island of Death’, on which nuclear weapons tests are conducted. The island seems to be something of a dirty secret, hidden away from the civilised world, and as such it becomes a tempting visit for the restless Cully and his party of pleasure-seekers. This feels like a metaphor for some sort of unhealthy ascetic Dualism, the separation of desires of the flesh from purity of mind, as if the latter can operate healthily without the former. Which is rubbish, of course – the sort of perversity of thinking typical of humanity across the ages.

Haisman and Lincoln (who asked for their names to be removed from the script prior to broadcast following disputes over the production team’s edits) clearly had some interesting ideas. The pair previously came up with the concept of the Great Intelligence-controlled Yeti in The Abominable Snowmen, similarly a darkness hidden within a structure of monastic discipline and purity, which leads me to wonder what the writers’ experiences might have been in this respect. It’s a shame that the intriguing themes of The Dominators are let down by a rather pedestrian, plodding script. It may be a while before I return to Dulkis.

War of the Sontarans

War of the Sontarans is the second episode of the six-part Flux series of Doctor Who, the last of the Thirteenth Doctor’s regular seasons (if any of her seasons – groundbreaking and innovative, divisive and flawed, and produced in large part under incredibly challenging circumstances – could be described as ‘regular’). It’s the fourth part of Flux that I have rewatched on this Randomised journey, following episodes four, three and five in that order, and the many constituent elements of the series’ hugely complex plot continue to make a bit more sense to me with each additional episode. Sort of. I mean, there’s still a lot that confuses me. It’s a bit like doing a jigsaw with the picture side face down, and only being given a sixth of all the pieces (not necessarily all from the same part of the jigsaw) at a time. But I’m sure it will all seem very, very satisfying when I’ve finished it. Only episodes one and six to go now, but I have no idea when the Randomiser will allow me to watch them.

Like all the other Flux episodes I have rewatched so far, the best thing about War of the Sontarans is how stunning it looks. It’s a hallmark of the Chris Chibnall-produced era that almost every story is a visual treat, packed with beautiful, imaginative, widescreen, cinematic vistas, and the Flux stories are the pinnacle of this. The bleak battlefields of Sebastopol, the Sontaran shipyard, Vinder’s ship hurtling through space, the Temple of Atropos, the Liverpool docks … all look fantastic. I understand many of people’s frustrations with Chibnall’s Doctor Who – those concerned with the scripting rather than misogynistic and racist bleating of idiots – and while I wouldn’t argue that the gorgeous imagery compensates for the tricky storytelling, it’s still something to be enjoyed. The bad things don’t always have to cancel out the good things.

The opening scene of War of the Sontarans is a case in point. The Doctor opens her eyes in some sort of dream state and finds herself standing beneath an enormous floating building – it looks like a decrepit haunted mansion, of many rooms. It’s a really great-looking scene, and I love looking at it and wondering. But it’s not really clear what this building is, or what it signifies, and as far as I remember it is not explained later in the series. I’m sure that most people, like me, assume that it is something to do with the Doctor’s forgotten past – her history as the Timeless Child – which could be really interesting, but it’s a huge frustration that this is a colourful thread left hanging loose. Our understanding is that Chris Chibnall knew that Flux would be his final series as Doctor Who’s showrunner, and it was always likely – presumably – that whoever followed him would not want to be bothered with tying up his unfinished storylines, so why was this question asked? It seems to be a bit like the Claire Bloom character introduced by Russell T Davies in the final story of his first run on the show. Was she the Doctor’s mother? Someone else? What did her mysterious pronouncements to Wilf mean? None of this was explained, so why introduce the questions in the first place?

We are left to wonder, to speculate. And that’s quite a fun thing for us fans who enjoy spending virtually every waking (and many sleeping) minute thinking about Doctor Who, but I still think it’s poor storytelling for a programme aimed at a much broader audience. Immediately before and after her vision the Doctor says 'The end of the Universe', and of course at the end of the Flux series she finds herself outside the known Universe, so perhaps this floating house is symbolic of what is to come - the house represents the entire Universe and she stands outside it, beyond it, at its end. I know that some people have linked the house to the Marc Platt novel Lungbarrow, but I haven’t yet got to that book in my reading of the Virgin New Adventures, so I don’t have an opinion on what that might mean. My take on the scene was that the house represents the entirety of the Doctor’s life, or perhaps their soul, as is often suggested in wisdom on dream symbolism (unsurprisingly, there are several theories about what houses represent but they are usually something along these lines; a quick internet search found this article which lists a number of different types of dreams about houses including the meaning of a house floating away, which can indicate a sense of instability and detachment from one’s roots, which certainly works in this case).

Houses seem often to be a prominent part of my own dreams. The most upsetting recurring dreams that I have ever had were a sequence in which I was having to move into a house (a regular-looking two-up, two-down sort of house in a residential street) in which there was one room (to the left as I walked in the front door, and down a bit, as if it was a basement) that filled me with dread. I can’t recall exactly what it was in the room, but I have residual feelings of something soft, rotten, decaying, and a repulsive smell. This dream came to me a few times during an unsettled period in my life, a transitional period spanning the end of my marriage, work and life in a particular place, and the settling in to a new life with my partner and soul mate Shaz, new work, new home. In addition to the physical changes of where and with whom I lived, new routines, and my relationships with my children, that was a time in which I was doing a lot of ‘inner work’, therapeutically, and working out how to manage various harmful issues, concerns and anxieties that had taken a hold on my unconscious and emotions over the years. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what the rotten room in the house represented, but I know it was important and I feel that I ‘banished’ that particular imagery by taking greater control over my conscious life. I still have loads of scary dreams – especially after I’ve eaten a lot of cheese before bed – but nothing that really disturbs me like that one used to.

I was just talking to Shaz about this and she made another good observation: that the Doctor’s floating house in War of the Sontarans reminds her of Dorothy’s house flying away in The Wizard of Oz. Both sequences were filmed in black and white, and in Dorothy’s case it seemed to represent a detachment from the real world (in which she was living an unfulfilled, ‘wrong’ life) and the start of a journey to awakening and truth – which seems to work for the Doctor in her quest to discover who she really is/was.

Not long after the Doctor’s mysterious house experience, Dan finds himself back on his home street in Liverpool, standing outside what ought to be his house … only it’s not there. That A Little Spark of Joy website I linked to earlier on has an entry for dreams about a disappearing house: they can be a message from your unconscious that you are struggling to connect with someone, or that your life is out of balance, or that someone in your life might be trying to manipulate or take advantage of you. All of which works pretty well for Dan in his Doctor Who arc, I think.

Dan lives – or is supposed to live – on Granger Street, Liverpool, a fictional road in the city leading up to the non-fictional stadium of Anfield. Seeing football referenced in Doctor Who is a relatively rare crossover of my two biggest fannish obsessions. The city of Liverpool gets a pretty good showing in the Flux series, and in War of the Sontarans in particular when Dan Dan the frying pan man takes on the Sontaran fleet berthed at the city docks.

I’m not a great enthusiast for Sontarans; at least, not since their first appearances in the early 1970s, in The Time Warrior and The Sontaran Experiment, each of which featured a lone representative with a genuinely menacing aura. These Sontarans (Linx and Styre, respectively) were played as cruel and powerful creatures, proper scary. Since then, and especially in the twenty-first century series, the Sontarans have been played more for laughs, and are diminished as a result. It was nice to hear Linx referenced in War of the Sontarans, though (Skaak: ‘This planet has defied us ever since the great Commander Linx first staked his claim in the ground of its feeble soil.’).

To be fair, I think this version of the warmongering clone race is the best of the new series versions, with their blotchier, battle-ragged heads, and placed for once in their natural environment of gritty conflict, rather than as scouts, outcasts or refugees from the battlefield as they have more often been cast in previous stories. The coming together of the Sontaran and British armies has the look of an impressive big-budget scene from Lord of the Rings. It’s quite the contrast from, for example, the cheap and tinny battle scenes from Battlefield, which I watched recently for this very blog, as one would hope for one episode made thirty-two years later than another.

Connections

I’m not sure what good it would do you, but if you wanted to really mix up your randomised Doctor Who rewatching experience, this is a rare example of a pair of stories that could be kind of stitched together as if one actually is intended to follow the other – if you’re prepared to squint really tightly and make all sorts of other allowances for illogical continuity. The Dominators ends on a cliffhanger of lava flooding towards the open TARDIS doors that looks a little bit like the burning waves of Flux energy cascading towards the open TARDIS doors at the start of War of the Sontarans. What if the Dulcian lava shocked the time machine’s systems into some catastrophic malfunction that replaced the 1968 occupants with the 2021 line-up? Stranger things have happened in this crazy show.

There are a few other connections between the two stories. Both feature a robed ruling council responsible for everything running smoothly. The Mouri in the Temple of Atropos are charged with keeping Time ticking over. Their existence is a strange reveal of Time as a distinctly separate force in the universe, locked in some sort of eternal conflict with Space. It’s an odd one, that doesn’t really fit with anything that’s gone before in Doctor Who, but interesting as another example of a Dualist perspective on life – such as the position of the Peace-lovin’ Council of Dulkis.

‘Where the hell have you been?’ … Or words to that effect. Dan has to explain his travels through time and space to his Mam Eileen and Dad Neville, while across the stars – and, presumably, across the centuries – Cully has to explain his dangerous travels to his own father, Director Senex.

‘Onward to domination!’ commands Sontaran Commander Skaak – a fitting call to arms for a race that shares a few similarities with the Dominators. Neither race appear to have necks, for a start. Or, at least, the wear collars so high that we can’t see any neck. Both species have a practice of experimenting on a native population prior to invasion, to assess either their suitability for slavery or the likely strength of their resistance (the captured Sontaran trooper Svild is tasked with this latter mission in War of the Sontarans, echoing the fact-finding expedition of Styre in The Sontaran Experiment).

Both Sontarans and Dominators have a fragile sense of pride. Skaak chides Svild for being captured by the British army: ‘The stench of your humiliation infects us all.’ Toba accuses Rago of unnecessary softness: ‘You've humiliated me before members of an inferior race.’

And both are hampered by failing power reserves. On at least three separate occasions in The Dominators the Quarks have to be recharged. The Sontarans need to refuel themselves for 7.5 minutes every 27 hours, which seems like a real design flaw. Both species could do with some additional charging cables for Christmas – they’re fairly good value in Primark.

Ultimately, the defeat of both Sontarans and the Dominators comes through the exploding of them within their own spacecrafts, which is a pretty horrible way to go when you stop to think about it. The Doctor expresses her disgust at Logan for blowing up the Sontaran fleet in the Crimea: ‘Men like you make me wonder why I bother with humanity.’ But let it not be forgotten that it was the Doctor who planted the seed bomb that destroyed the Dominators’ ship, with little sign of remorse.

One of The Dominators’ themes seems to be the futility, the weakness, of pacifism, with the Doctor and Jamie urging the Dulcians to fight back against the Dominators, recalling Ian’s attempts to put some fire into the bellies of the Thals in The Daleks. But in War of the Sontarans the Doctor is critical of the soldiers. It’s not uncommon to see the Doctor taking different positions on pacifism and violence across the history of the show. Obviously there are inconsistencies caused by changing writers and changing values over the course of time, but I suppose one could also see it within the narrative as an illustration of the conflicts within the Doctor, themselves a changing personality over the course of time.

留言