Genesis of the Daleks vs. The Witchfinders

I’m heading back in time from last week’s stories on both Skaro and Earth, as the Randomiser directs me to Genesis of the Daleks by Terry Nation (first broadcast in March and April 1975) and The Witchfinders by Joy Wilkinson (25 November 2018).

Genesis of the Daleks

Tom Baker, Lis Sladen, David Maloney, Robert Holmes, Terry Nation, Philip Hinchcliffe, Dudley Simpson, Dick Mills, Ian Marter, Michael Wisher, Peter Miles. In Doctor Who production terms, Genesis of the Daleks sits at the Galácticos level. You couldn’t really ask for a more prestigious team to put together a Daleks origin story, introducing us to their creator and re-energising the Dalek mythos twelve years after they first became an intrinsic part of British popular culture. And the dream team pull it off – GOTD is undoubtedly one of the very best Doctor Who stories ever made.

Like the majority of Doctor Who fans, I’m sure, it’s a story with which I am very familiar, but not overly so; it can be appreciated over and over again. Many of my generation will have owned the BBC soundtrack release of GOTD as youngsters – and so know the sound of the story even more than the look of it. I could probably quote this one more than any other Doctor Who story, so many times have I heard it. Lines such as ‘Daleks? Tell me more’, ‘No tea, Harry’, ‘I sent Harry and Sarah in there’, ‘Thank you. That’s what I wanted to know’, ‘That power would set me up above the gods’, ‘Do I have the right?’ resonate deeply.

The peculiar whims of the Randomiser brought this story up for me to watch immediately after its sequel, Destiny of the Daleks, so I have found myself watching it on this occasion as a prequel – albeit one set thousands of years (one assumes) before the events of DOTD. What did I notice, watching the two stories this way round? Skaro – or at least the land surrounding the site of the old Kaled bunker in which Davros is exterminated at the end of the story – looks fairly reasonable as what would become the quarry-like remains visited by the Doctor and Romana in DOTD. It’s rocky and rubbly – there’s a lot more metal debris lying around, but this presumably would have been tidied up after the end of the Kaled-Thal war. The Daleks are properly introduced as angry, hate-motivated, genetically-manipulated mutants inhabiting battle armour shells, rather than the logic-driven robots described in DOTD, which makes that mistake in the latter all the more unforgivable. A Kaled soldier comments that there have been rumours of the Thals developing robots, but we hear no more about this; could their work over the following centuries have led to the eventual development of the Movellans to counter the threat of the Daleks?

Episode two of GOTD makes various references to making snap judgements about people based on how they look. Sevrin, of the Mutos, questions why his kind should always have to kill beauty, when he and his companion capture Sarah. They don’t know who she is, only that she has no deformities or imperfections, which to his mind makes her worthy of mercy. His whiffy pal Gerrill sees her physical appearance as proof that she must be a Norm, and therefore must be killed. Both arguments are flawed, of course. ‘You can’t always judge by external appearances,’ the Doctor tells Ronson later in this episode. There does seem to be a visual difference between the Kaleds (generally dark haired) and the Thals (lighter hair), which I imagine doesn’t help their ‘judge on sight’ inclinations. Elsewhere in the story it is implied that differences between the two tribes do run deeper than the colour of their thatches. The Kaleds are on some sort of path of genetic deterioration, which doesn’t seem to be a problem for the Thals – as we have seen in stories set centuries after GOTD (The Daleks, Planet of the Daleks), they retain their human form long after the Kaleds have all turned into slimy mutants.

There is much talk in the Kaled ranks of patriotism alongside that of genetic purity, which makes one think not only of twentieth-century fascism as obviously intended but of the increasing tolerance – encouragement, even – of racism, xenophobia and nationalism in the UK, US, European mainland, South America and elsewhere in the world today. It’s both shameful and terrifying, and we should all do all that we can within our own spheres of influence to stand against it. Doctor Who has the potential to play its part. It has a platform of cultural and social influence in this country, and I do expect it to continue exercising its role to fight the good fight.

The Doctor’s ‘Do I have the right?’ scene in which he questions whether or not he should stop the Daleks from ever having been created has iconic status in the series’ history, although it always leaves me feeling slightly disappointed. It’s a good moment for Tom Baker, Lis Sladen and Ian Marter – such a confident, audience-engaging team, playing up a big moment in the story and delivering it with suitable levels of momentousness. But, I don’t know, it seems as though it doesn’t deliver somehow. Maybe because it’s asking a question that seems impossible to answer in a satisfactory way, and any position on it taken by the show over the years seems to have been contradicted by itself on other occasions. Perhaps that’s the point – that it’s all paradoxical and there are no easy answers, and the frustration I feel is the intended response.

I have fond memories of Harry Sullivan even though he wasn’t one of the Doctor’s companions for very long. Come to think of it, we probably never even saw him inside the TARDIS, did we? But he was one of the companions when I first started watching the programme, and I think of the Doctor-Sarah-Harry triumvirate as the original model for a TARDIS crew. He has a good rapport with the Doctor, and likes to make crummy Dad jokes, which I find endearing. GOTD offers, perhaps, Harry’s most heroic moment when he rescues the Doctor from the land mine on which he stood; the subsequent smile of genuine gratitude and appreciation from Doctor makes me feel good, so I must empathise with Dr Sullivan in some way.

The Daleks in GOTD only cut loose right at the end, turning on their creator like the vicious, untrustworthy devils that he bred them to be. Before that moment they carry an air of silent menace, potential threat, as only the Doctor and Sarah (and us, the viewers) know what they will become. On a number of occasions director Maloney conveys this dark potential visually with a literal foreshadowing – we see the shadows of Daleks approaching around corners of the story’s many corridors before the appearance of the monster itself.

The stand out performance in GOTD has to be awarded to Michael Wisher for the stunning portrayal of Davros. What an incredible, commanding performance that was – he’s an absolute scene-stealer. There have been countless memorable Doctor Who villains over the decades. The character is a crucial part of the Who formula. Generally speaking the Who villain is a rather hammy figure – larger than life, pantomimey even; it’s probably the best way of holding one’s own in a role which sets one in direct opposition to the charismatic Doctor figure. Even the great Roger Delgado gave a rather stagey performance as the Master – probably the show’s most celebrated bad guy prior to 1975. But Wisher’s Davros is on a different level: cold, still, controlled yet furious, fascinating, utterly humourless, and terrifying. None of the subsequent Davros actors have being able to match what he delivers, which is not to criticise several other fantastic performances – just to acknowledge something very special in the history of Doctor Who.

The Witchfinders

‘My granny used to say there was enough wonder in nature without making things up,’ Willa Twiston tells the Doctor and Yaz. I think that’s a really good line from one of the stronger Series 11 stories. I’ve spent a lot of my life listening to stuff people have made up about things we can’t see. It’s a fairly good definition of theology, and religion is the application of that made up theology for the purposes of power and control. I’ve also spent a lot of my life lost in wonder at the natural world – whether it be the roll of a valley, the magic of a wood, or the infinite vista of a sky full of stars. I’d rather commit my spirit to these winds than to the boundaried walls of a church or cathedral. There’s science to explain all of those natural wonders, but also an indefinable quality – a spirituality of nature. There’s no need for theologians to try to explain that spirituality, because there’s no means (usually) to exploit it for their own power. It just is – it’s there without explanation, and that’s fine; we can just appreciate it.

There’s a lot of that spirituality of the natural world in The Witchfinders. Cold, damp, muddy hillsides, misty lakes and spooky forests. ‘In the water. In the fire. In the air. In the earth.’ This is probably my favourite kind of Doctor Who. As a child, seeing a new landscape full of places to run and hide and explore usually sparked my desire to run off and play Doctor Who – to invent a new adventure for my imaginary travels with the Doctor, Sarah and Harry. And yes, I still get that urge sometimes today, unable to act upon it because a grown man just shouldn’t do that sort of thing. But that’s where my soul is; that’s my spirituality.

I want to dislike King James in this story, of course I do. He ticks all the boxes for me: he’s a royal, he’s a religious leader, he’s a murderous persecutor, he’s responsible for the King James Bible (I know a fair bit about Bibles, and the KJV is one of my least favourites). But it’s hard to really hate any character played by Alan Cumming. I mentioned, when writing about Davros a few paragraphs ago, the tendency for Doctor Who villains to play up the comedy, and Cumming certainly does that here – but to great effect, and he’s a joy in every scene. His unpacking of his box of artefacts – torture devices, charms, brooches and prickers – is one of my favourites; very funny.

Despite this, The Witchfinders doesn’t fail to demonstrate the evils of James’ age, in particular the witch hunts that increased under his reign. What truly terrible time to be a woman in England. I mean, I don’t think there have been many good times, but there’s a particularly nasty culture of misogyny on display here, from the blaming of women (especially women with an aspect of ‘otherness’) for the blight of the land to the pressures facing Willa when left to live alone. One even feels a little sorry for Becka Savage when it’s revealed that she demonised her grandmother and other women as a defence against the alien infection inside herself; she had abandoned her own family by marrying the village squire, but it probably would have felt that allying herself to a man was a choice of survival rather than preference.

There’s an observation made on the TARDIS Data Core Doctor Who wiki page that The Witchfinders is the first story in which the Doctor herself is seen facing adversity in a historical setting because of her gender, as she is forced to undergo trial by drowning. And there’s a good moment of female solidarity between Yaz and Willa, in which Yaz recognises the severe stress being suffered by Willa, relating it to a particularly tough year of bullying she received at school. While I’d hesitate before comparing that to being accused of witchcraft in the seventeenth century, it’s relevant to context and adds to the strong thematic thread of the story.

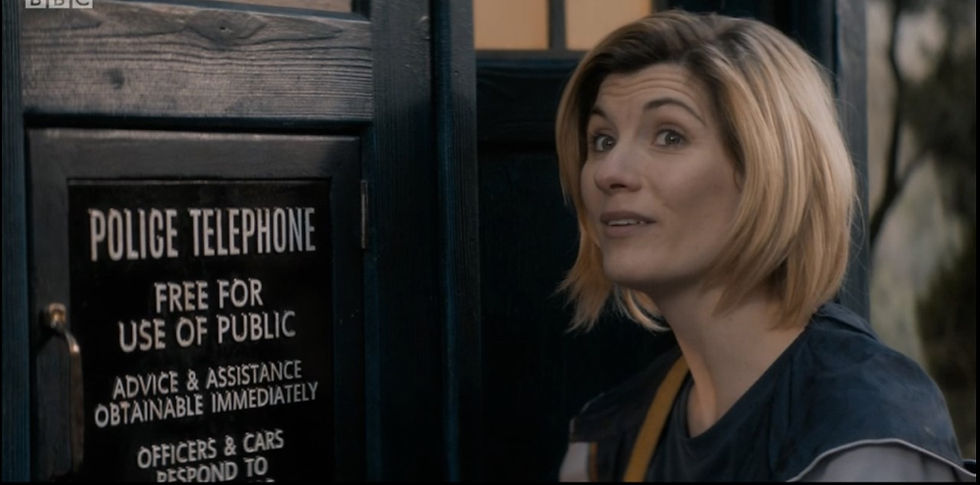

What makes The Witchfinders especially remarkable (in Doctor Who terms) is its predominantly female cast, and the fact that it is both written and directed by women (Joy Wilkinson and Sallie Aprahamian respectively). This is exactly as it should be for a story about female experience and perspective, and how it should have been so much more throughout the show’s history – whatever the themes. Doctor Who’s first producer was a woman, its first story included four important female characters among its leads, and yet over the following decades this crucial dimension of the show’s make-up was lost. Doctor Who as an institution – production, narrative and fandom – became suffocatingly male-dominated; there were entire stories that featured only one female cast member (Genesis of the Daleks managed to find room for two), and female characters were regularly patronised and objectified.

Was the sexism of Doctor Who a product of its times? Yes, but then, so were the witch-hunts. It’s not something to be ignored or excused, and absolute credit should go to the creative teams of the Jodie Whitaker/Chris Chibnall era of the show for the revolutionary steps they have taken towards redressing the balance. It has not been without severe, vicious resistance and criticism from some of the darker corners of fandom, but on the other hand there seems to be much evidence to suggest they broadened the appeal of Doctor Who – across both gender and generations. This is hugely important and I think will be viewed positively in future histories of the show.

Connections

Genesis of the Daleks and The Witchfinders both open in inclement conditions, with the Doctor and their travelling companions wandering across cold, misty landscapes.

Perhaps there’s something in the air that prompts both Harry and Ryan to crack an anachronistic dad joke. ‘It's like finding the remains of a stone age man with a transistor radio,’ says the Doctor. ‘Playing rock music?’ quips Harry. Ryan describes the woodland gathering at Bilehurst Cragg as ‘Ye olde hipster pop-up happening.’ Funny guys!

Both stories have a show and tell scene. The Doctor empties his capacious pockets in GOTD, revealing, among other things, a yellow yo-yo (see also The Robots of Death and The Girl Who Died), a magnifying glass, and an etheric beam locator (‘useful for detecting ion charged emissions’). In The Witchfinders, King James unpacks his capacious box of witchfinding tools, revealing, among other things (‘to ward off evil spirits’), torture implements, charms, and a wide selection of body parts.

The Doctor comes face to face with an angry slimy alien in a jar in both stories – proto-Daleks in the Kaled mutants incubation room, and a little bit of muddy Morax trying to get back into the reanimated body of Willa’s nan.

‘I need you all to remember the most important thing about dips into the past. Do not interfere with the fundamental fabric of history,’ the Doctor warns her companions at the start of The Witchfinders. This is the central theme of GOTD too, as the Doctor resists the opportunity to interfere with the history of the Daleks (well okay, mostly resists).

Both Davros and King James are far less disciplined, although it’s their respective futures that they want to change, with the Doctor’s knowledge of what is still to come rather than what has gone before. ‘Before you die, I want answers. I wish to know all the secrets of existence,’ James demands of the captured Doctor. ‘With that knowledge, there shall be no defeats!’, screams Davros. But the Doctor’s Witchfinders reply, ‘True knowledge has to be earned,’ is a nice line.

This villainous pair make for an interesting comparison. Both are creators of something iconic that will outlive them and span many ages to some, influencing millions and millions of lives. Okay, King James didn’t actually write or provide the translation for the King James Bible, but he enabled its creation; equally, perhaps it is true to say that while Davros was responsible for the creation of the Daleks, he was an absent father for hundreds or thousands of years after the first day or so, so what they became was as much down to their own self-determination than his design. ‘A man's heart deviseth his way: but the Lord directeth his steps.’ (Proverbs 16:9 KJV)

There is an implication in The Witchfinders that King James’ dysfunctional childhood is in large part responsible for how he acts as an adult. ‘It's a long, sad story. A tragedy,’ he tells Ryan. ‘My father died when I was a baby … My father was murdered by my mother, who was then imprisoned and beheaded … I was raised by Regents. One was assassinated, one died in battle, and another died in suspicious circumstances. There have been numerous attempts to kidnap me, kill me or blow me up. It's a miracle I'm still alive.’ If it’s true that this influenced James’ unsettled path through life, what might we guess about Davros’ upbringing? I remarked upon his own competitive, bullying father instincts in my review of Destiny of the Daleks, which suggests he might have had some nasty experiences of his own as a son.

Whatever the reasons, one of these men grew up to be a scientific purist and the other a religious purist – both fanatics, and both masterminding grandiose schemes outwith the boundaries of morality. Here's a Venn diagram of operating principles: science, the supernatural, and conscience. The brain, the soul, and the heart. Could we argue that the Doctor occupies the centre spot? Their commitment to science and morality are fairly clear, but there have been occasions on which they have been open to spiritual dimensions too.

Comments