The Ultimate Foe v. Eve of the Daleks

I’m on jury duty this week, in court to pass judgement on the Sixth Doctor’s final story The Ultimate Foe (part one by Robert Holmes and part two by Pip and Jane Baker), from 29 November and 6 December 1986, then to New Year’s Day 2022 to label and store my opinions on the Thirteenth Doctor’s Eve of the Daleks (by Chris Chibnall).

The Ultimate Foe

As with the ‘Flux’ new series 13, I decided to treat the constituent stories of ‘The Trial of a Time Lord’ classic season 23 as standalones for my randomised story watching, rather than watching the whole season in order in one go. The Ultimate Foe covers the final two episodes of that season, but while it is presented as a story in its own right – with a beginning, a cliff-hanger middle, and an end – it’s also a game of two halves, with different authorship for the two episodes (Robert Holmes wrote part one, but illness prevented him completing it so Pip and Jane Baker wrote part two) and the pair poorly woven together in large part – so the received wisdom seems to be – because of a breakdown in the relationship between script editor Eric Saward and producer John Nathan-Turner. Consequently, it’s a story without much thematic depth and a messy, disappointing, frustrating end to the Sixth Doctor’s run.

The story has some enticing visuals. The dark, Victorian pottery mill in which the Valeyard makes his base within the Matrix, and the terrifying hands that pull the Doctor beneath the sand are examples of the sort of British gothic horror that can be Doctor Who at its very best. There are some grandiose lines of script – ‘A farrago of distortion which would have had Ananias, Baron Munchhausen and every other famous liar blushing down to their very toe nails’; ‘There's nothing you can do to prevent the catharsis of spurious morality.’ – and ideas that sound promising – the Matrix has been compromised!; insurrection on Gallifrey!; the Valeyard is the Doctor! – but none of them really go anywhere or have any lasting impact. It all feels very thin.

In keeping with all this showmanship, the cast of the story comprises big names and big personalities of Seventies and Eighties British TV: Colin Baker, Bonnie Langford, Tony Selby, Michael Jayston, Linda Bellingham, Anthony Ainley, Geoffrey Hughes and James Bree. There is a lot of talent there, of course, but not a great deal of subtlety. There are no fresh new voices on display, but a lot of verbose scene-stealers. The Doctor v. the Valeyard v. the Master in itself feels too crowded a stage for just two short episodes, so adding all those other larger than life performers gives the whole thing a bit of a Halls of Valhalla feel. Too many MVPs!

TUF picks up and continues some of the most important ideas introduced to Doctor Who mythos by Holmes in his earlier story (broadcast almost exactly ten years earlier), The Deadly Assassin: the corrupt, bloated and hypocritical nature of the Time Lords (‘The oldest civilisation, decadent, degenerate and rotten to the core,’ accuses the Doctor, in one of the story’s better speeches), the Matrix, and the twelve-regeneration limit of Time Lord existence. While TDA was set in the Capitol’s political arena, TUF shows us that Gallifreyan corruption extends also to the society’s law courts. Bellingham’s Inquisitor makes lofty pronouncements about contempt of court, and even the Doctor seems very happy to accept that Gallifreyan rule of law must prevail, but it soon becomes apparent that the whole charade has been compromised by malevolent agencies – both the Valeyard and the Master are manipulating events like cackling puppeteers.

Watching all of this in Britain in 2023 all seems very familiar. As our government consistently twists and flouts the law to its own ends, and the leader of the opposition makes grandstanding speeches about values of law and order while refusing to honour the rules and promises of his own party, there’s nothing particularly shocking about judicial corruption on Gallifrey. This is how Establishment works.

The Trial of a Time Lord series is generally accepted to have been conceived as a thinly-veiled metaphor for the putting on trial of the television series of Doctor Who itself, by Michael Grade and other controllers at the BBC. With that it mind it was probably quite brave of Nathan-Turner, Saward, et al. to portray the judicial system examining the Doctor as rotten to the core. Again, it would seem less controversial today as the crookedness of higher governance at the BBC has been revealed and is more widely accepted as being corrupt.

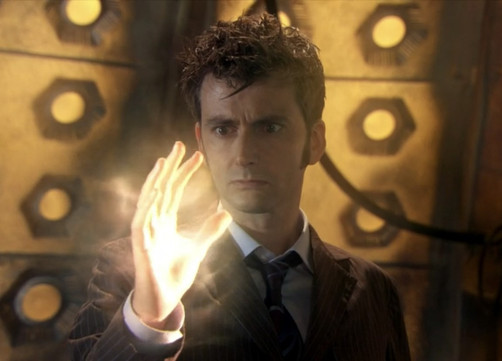

Chief prosecutor, the Valeyard, is revealed in TUF to be a future version of the Doctor – some sort of splinter incarnation from between the Doctor’s Twelfth and Thirteenth personas. The Valeyard is, according to the Master, an amalgamation of the darker sides of the Doctor’s nature. In later years, it is established that the Doctor’s twelfth regeneration was that which took place at The End of Time (David Tennant into Matt Smith); this was the most drawn out regeneration process we had seen the Doctor undergo at this point in time, so we can speculate that this unusual process may have been what caused the creation of the Valeyard, leaking out in some of that glowing orange time energy that the Doctor was trying to hold in before he eventually got back to his TARDIS to regenerate properly. The Tenth Doctor had been battling with the dark side of his nature towards the end of his era, trying to resist the temptations of breaking the laws of time, so perhaps he managed to eject some of that before regenerating (or perhaps it got sent back into the void with Rassilon and all of Gallifrey) and those rejected elements of his self separately became the Valeyard. Who knows?

However he came about, the Valeyard is an interesting idea. Do we all have elements of ‘evil’ within us? There’s a psychotherapeutic idea that we all have a shadow side – the repressed id – that it can be helpful to engage with and understand as part of a path to self-healing or enlightenment. What might our own shadow look like, and what does that tell us about how we see ourselves and who we would like to be (our ego ideal)? The Valeyard tends to define himself not so much as a personification of evil, but as a version of the Doctor ‘uncontaminated by [his] whims and idiosyncracies’, or by his ‘romantic nature’; by default, the character of the Doctor is defined as someone rather eccentric, rather than necessarily as Good. I think this is a fair assessment, in keeping with what we have seen of them in other stories across the decades.

Part of the problem of the aforementioned overloading of this short story with ‘big’ characters is that most of them get rather sidelined. The Master seems an utterly unnecessary addition to the script. He appears on a big screen in the Time Lords’ court room, chuckles a bit, and then stumbles straight into some sort of stupid trap with a limbo atrophier (whatever that is supposed to be). Glitz wanders about the place with a cuddly grin and churning out ridiculous barrow-boy phrases, and we are supposed to believe that he is one of the most devious wide boys in the universe. And Mel introduces herself to the court ‘as truthful, honest, and about as boring as they come’, which I’m afraid she goes on to prove. I always found it quite difficult to like Mel, but an amalgamation of the darker sides of her nature would probably make a much more interesting character.

Eve of the Daleks

All but the closing scenes of Eve of the Daleks takes place within a period of ten minutes or so, just before midnight on New Years’ Eve. The human cast of the show comprises five people, all of whom are exterminated during the opening pre-credits sequence. They all come back to life again, of course – several times – and that ten-minute period is repeated again and again (minus a minute each time) through the course of the episode, because this is a story about being caught in a time loop. It’s a clever story, and a fun one, befitting its holiday broadcast slot – but the setting of it makes it seem small, somehow. It’s a throwaway story, apparently of no consequence, lacking a sense of the epic or bombastic.

But some of the most important things in the universe occur at the smallest of scales, and this is the one which kick starts the simmering love story between Yaz and the Doctor, as the Doctor is pretty much told (by Dan – blabbermouth!) that Yaz is in love with her.

Does the Doctor love Yaz? I know there’s a huge body of support for the idea that she does, even though I don’t think she ever says as much on screen. Personally, yes, I think she does. The narrative of Thirteen’s last few episodes makes more sense that way – it’s even more of a sacrifice for the Doctor when she feels she has to friendzone Yaz, and when she says goodbye before regenerating. Also, I think there’s something in her eyes when Dan blabs that Yaz has feelings for her – a fear, a recognition that she knew all along, that she has similar feelings? It's probably down to each of us how we interpret it, but my gut here is to go Team Thasmin.

How many times has the Doctor been in love (according to televised canon)? I’ve tried listing of all those people either seen or implied to have had something goin' on with the Doctor: Cameca, Jo (more of a parental love, perhaps, but it's interesting that she chose someone so similar to him and that he was so upset to lose her to another man), Sarah Jane, Romana, Todd (from Kinda; she and Five were clearly into each other, even if just in a boring science teachers kind of way), Grace, Rose, Jack, Madame du Pompadour, Martha, the Master/Missy, Astrid, River Song, Lady Christina, Amy, Idris/the TARDIS, Marilyn Monroe, Clara, Elizabeth I, Cleopatra, Yaz. I’m sure there are others I've missed.

I reckon most of these relationships fall short of the Doctor actually being in love – most of them were most likely just a fancy or a flirtation, a snog, a Gallifreyan sexy time, unrequited love on the part of the companion or even a very Doctorish misunderstanding. Those people with whom the Doctor has actually been in love – deep, serious, romantic love, reciprocated – are, in my opinion, probably Romana, Rose, the Master/Missy, River Song and now Yaz. Rose and River are self-evident, the Master/Missy is heavily implied and seems likely, and while it was never spoken I just felt it was there between Romana (especially in her second incarnation) and the Doctor – you could almost see the bonds between them.

Getting back to EOTD, it has the feel of a video game, or perhaps an escape room scenario, as much as a regular Doctor Who story. There’s a problem to be solved: how can the Doctor and her friends escape the time loop? It’s a well set up idea. They are trapped in a dark building – a maze of lifts and corridors – and no matter where they run, the Daleks find them and shoot them. It has the feel of one of those hopeless nightmares in which you are foiled again and again, whatever you try to do.

In all honesty, I got a bit lost over the ins and outs of the plans they tried to execute each time the clock re-set. It’s a problem with these Chris Chibnall stories that I’ve mentioned before: so much depends on following the spoken explanation of what’s going on, rather than being able to follow more visual cues of the language of direction, acting and editing. So I was able to enjoy the story at the sort of level that I enjoyed Doctor Who as a child – appreciating the action, the scares and the funny bits, without really following the plot logic. Maybe that’s not necessarily a bad thing?

Those set piece moments included a scene in which Dan faces up to one of the Daleks alone (‘All right mate? You new here?’), and ends up running around him on the inside of the Dalek’s revolving gun-stick, which seems like quite a clever move. This scene made me laugh, and was a nice moment of comedy for an actor whose first profession is as a comedian but didn’t really get too many opportunities to demonstrate those skills during his short time on the show.

When I see EOTD mentioned on social media, the most common talking point seems to be the character of Nick – in particular, how much of a danger he is revealed to be with his labelled collection of previous girlfriends’ belongings (I remember Shaz and I exchanging raised eyebrows at this bit on first broadcast), and whether or not it’s a good idea for Sarah to hook up with him at the end of the story. To be fair, it’s not ignored within the script, as everyone else’s expressions suggest that they think the object collecting is a bit of a red flag, and Sarah calls him a weirdo, but later concludes that he’s a ‘good-hearted weirdo’ and so probably okay. After this repeat viewing of the story, my reading is that Nick probably is okay – he genuinely seems like a harmless, well-meaning if naïve sort of guy – but making a gag out of a weird sort of habit which would also be a sinister tell for a stalker is an unwise scripting choice for a family show such as Doctor Who.

Behind the love stories, the central theme of EOTD seems to be persistence, resilience. It must be bloody annoying for each of the characters to keep suffering agonising extermination as they do, and it must take a lot to pick themselves up and keep going. We have had a similar period of time here at home over the last few months – challenges with work, COVID, the miseries piled upon us all by government, energy companies, the media and all those other bastards, and various other difficulties – have made it a really tough time, and with no respite one sometimes wonders what keeps us going each new day. Well, we’re fortunate enough to have each other, and people around us who we love and who love us. In the (excellent) words of the Doctor: ‘We try, it doesn't work, we try again. We learn, we improve, we fail again, but better, we make friends, we learn to trust, we help each other. We get it wrong again. We improve together, then ultimately succeed. Because this is what being alive is. And it's better than the alternative. So come on, you brilliant humans. We go again and we win.’

Connections

I couldn’t find much to connect these two adventures. There’s a desk bell at the reception point of both The Fantasy Factory in The Ultimate Foe and ‘Elf’ Storage in Eve of the Daleks, but sadly it doesn’t get dinged in the latter story.

Dan, a Scouser, is most upset at finding out he has to spend New Year’s Eve in Manchester (and to be fair, it doesn’t turn out to be a great one for him). In TUF the character of Popplewick is played by Geoffrey Hughes, who famously for many years played a Scouser in Manchester, Eddie Yeats in Coronation Street.

‘Daleks, Sontarans, Cybermen, they're still in the nursery compared to us,’ claims the Doctor in TUF, protesting the Time Lords’ scheming. It’s a rare on-screen reference to both Daleks and Sontarans in the same scene, repeated by the Doctor in EOTD (DALEK: ‘Using the Flux to destroy the Dalek war fleet.’ DOCTOR: ‘That wasn't my idea! That was a Sontaran stratagem that I hijacked.’). A Cybermen fleet was also destroyed by the same Sontaran stratagem, so all of the ‘Big Three’ monsters are sort of referenced here, if not all named.

Because they held the Doctor responsible for this mass destruction, the Daleks decided that she must be executed, without a fair trial. This isn’t the first time she has faced such a scenario: in TUF, the Doctor is found guilty of genocide and sentenced to death, again without the benefit of a fair trial. Space justice is a rough business.

Comments